*

In many ways the process of my work is an ongoing experiment to see how I can open myself to a larger field of experience and information. At times I live nomadically, wandering, going from project to project and city to city. I find myself moving through space and responding to experiences in a way that’s very different from the way you do if you stay in one place. A moment that might ordinarily just flash by now makes a deep impression on you. Your sense of time expands or contracts, and you become extremely sensitized to things you might not have noticed before. As I found myself in constant motion, I became increasingly attracted to in-between places, places that were not destinations, places that were somehow in limbo or were outcast and passed by.

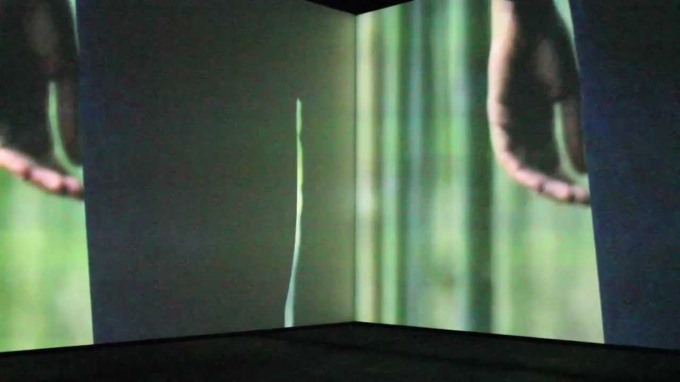

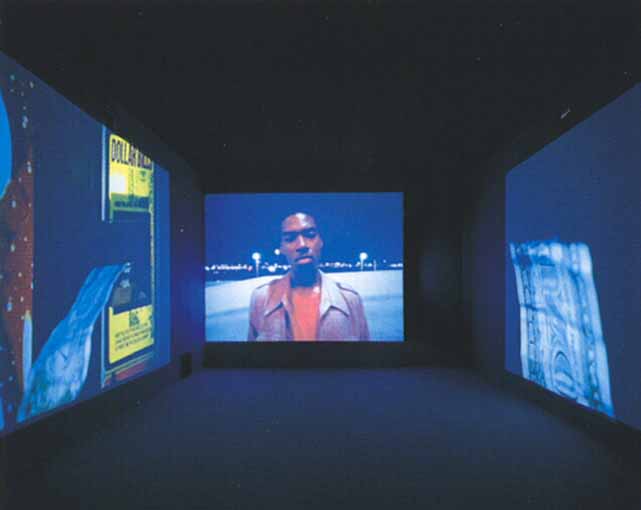

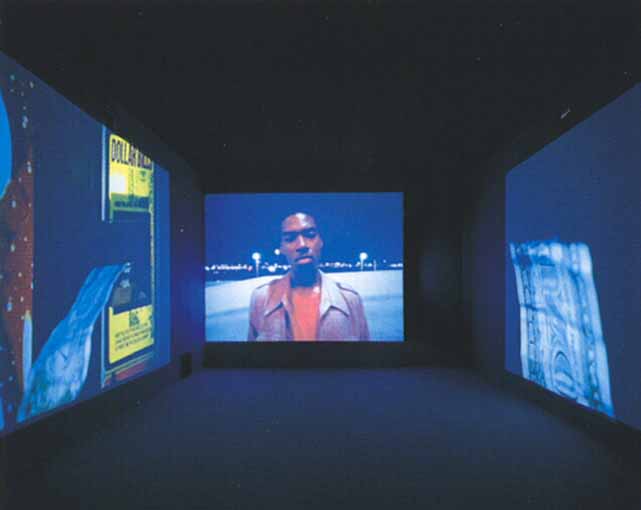

Electric Earth is a compendium of these in-between places and neutral spaces. It’s structured around a single individual, whom I imagined as being the last person on earth. He is in a state somewhere between consciousness and unconsciousness, and he is traveling through a seemingly banal urban environment in the moments before nightfall. As he moves, the world around him–a satellite dish, a trash bag spinning in the air, a blinking streetlight, a car window–begins to accelerate.

I wanted to see if I could break open the linear trajectory of his journey, which I imagine as a kind of walkabout, and unlock a different perception of the environment he moves through. Taking a walk can be an uncanny experience. Propelled by our legs we find rhythms and tempos. Our bodies move in cycles that are repetitious and machinelike. We lose track of thoughts. Time can slip away from us; it can stretch out or become condensed. Sometimes, the speed of our environment is out of sync with our perception of it. When this happens, it creates a kind of gray zone, a state of flux that fascinates me. The protagonist in Electric Earth is in this state of constant flux and perpetual transformation. The paradox is that it also creates a perpetual present that consumes him.

Electric Earth appears to be situated in a single time and place, but it’s actually a constructed, hybrid landscape composed of material gathered over time. In making it, I specifically experimented with treating each element, no matter how small, as if it were as important as every other element, and I tried to give every detail equal weight in the overall narrative. I wanted to see if I could create an organic structure–like a strand of DNA, where every bit of information, every chromosome, is critical–through accumulations of small events and actions. My goal was to create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Time is also a critical subject of this work. I broke up Electric Earth into a sequence of spaces because I’m not interested in constructing something linear. Film and video structure our experience in a linear way simply because they’re moving images on a strip of emulsion or tape. They create a story out of everything because it’s inherent to the medium and to the structure of montage. But, of course, we experience time in a much more complex way. The question for me is, How can I break through this idea, which is reinforced constantly? How can I make time somehow collapse or expand, so it no longer unfolds in this one narrow form?

Electric Earth is composed in a way that I hope doesn’t predetermine its meaning. It’s important to me to preserve the enigma of actions and events. I am not interested in illustrating or making a statement about a specific place. The landscape doesn’t refer to a city like Los Angeles or New York. Rather, it’s an amalgam of different places that have one thing in common: They’re all in a state of continuous motion. The landscape in Electric Earth is stark and automated, but the electricity driving the machines is ultimately more important than the devices it drives. It’s what the protagonist responds to, and what puts him in motion in turn.

The deluge of information we’re confronted with today is inescapable, and I hope this work is seen as a document of its ever-increasing pace. You can’t rely any longer on the kind of perceptions that come built into a specific medium or genre. It’s not really possible to limit yourself to a single language anymore–like, say, the language of abstract painting, or Hollywood, or music, or performance. These have all become rigid systems on the one hand, and totally porous on the other. With each piece I try to work with the language of images and the tools that are available to me, and strive to carve some kind of personal perception out of this endless flow of information we call experience. We all strive for that, I think. Otherwise, like the protagonist in Electric Earth, we can easily become lost, and vanish.

“A lot of times I dance so fast that I become what’s around me.” So says the lone protagonist of Electric Earth, 1999, Doug Aitken’s hyperkinetic fable of modern life in the form of a sprawling eight-screen installation that took home the International Prize at last summer’s Venice Biennale. An uncanny cross-pollination of genre conventions sampled freely from music video, documentary, and narrative film alike, the work forged a weirdly precise portrait of urban angst, wedding installation to the vernacular vocabularies of cinema and dance. In Electric Earth as in Aitken’s previous works, the landscape–here an anonymous expanse of urban wasteland–isn’t a passive backdrop for human action, but rather its driving force. The blinking traffic lights, panning video cameras, and automatic car windows create an environment of jerky, accelerating rhythms that Aitken’s young black protagonist begins to mimic, as if involuntarily. Projected on enormous screens in three adjoining rooms, Electric Earth is itself an immersive landscape of motion and fractured information, which viewers are meant to experience as much as to watch.

text source: ubuweb

*

http://www.dougaitkenworkshop.com/

http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazine/doug-aitken/

http://www.ubu.com/film/aitken.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.